About this manuscript

See Lesson 11 for background on the al-Musnad al jāmiʿ by al-Dārimī. As noted in Lesson 12, this manuscript was produced from oral reading sessions, and, as the manuscript also evidences, it was re-read after its initial copying. Each of these readings were marked on the manuscript and corrections were made accordingly.

Noting Corrections

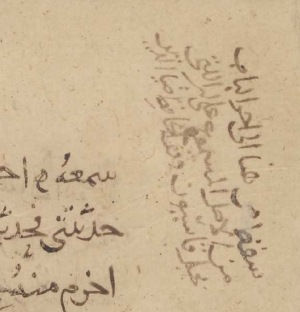

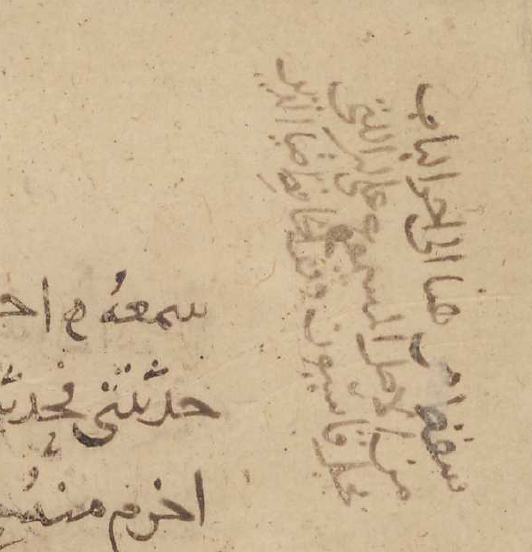

The aim of collation was to make corrections to the transcribed text and mark points of interest to scholars, and the ways in which marks and corrections were added to manuscripts followed conventions. Annotations were invariably made in the margins (ḥāshiya or hāmish), not in the main text block itself (the matn). The place in the text where something was found to have been omitted or misread is often indicated by a reference mark (ʿaṭfa), which often was written in a curvilinear form, or resembling a v or ٢). Throughout the Arabic manuscript tradition, corrections in the margin were usually accompanied by the word ṣaḥḥ صح , correct, or simply by ص.

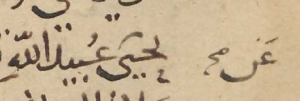

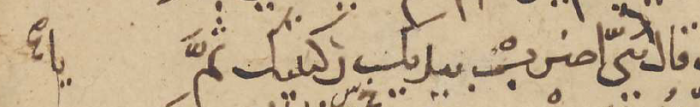

In the correction mark illustrated to the right, the original copyist wrote يحيى عبيد الله (personal names "Yahya 'Ubayd Allah") but the text should have been يحيى عن عبيد الله ("[from] Yahya on the authority of 'Ubayd Allah"). In the process of checking, this omission was noted, and the correct word to be added to the manuscript (عن) was written in the margin alongside the abbreviation صح, with a curvilinear ʿaṭfa mark written in the body text to indicate where the insertion should be made. A similar example is the text below, where the particle يا was left out in the original copy, and inserted in the margin with a note صح to indicate the correction, and its place in the body text is marked by a curvilinear ʿaṭfa

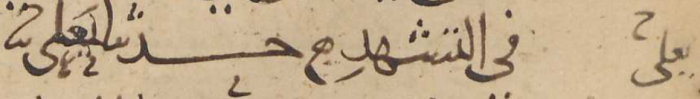

A range of other symbols might appear in the margins of manuscripts following collation. Symbols include marks noting that a word or claim was wrong ( غ for غلط) or should be inverse (ل for بدل) or to identify a marginal gloss ( ح for حاشية ). An example of the marginal gloss in the present manuscript is a mark ح to clarify the name يعلى which had been written a little unclearly by the copyist in the body text.

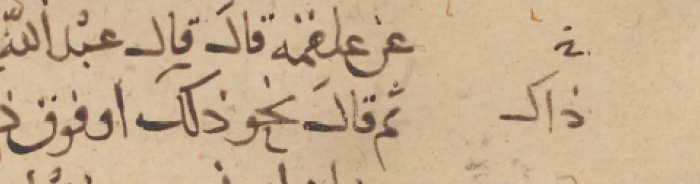

Another common marginal annotation produced by collation is خ: i.e. nuskha ukhrā (another version): this note is inscribed where the manuscript was checked against more than one older copy of the book, and via the comparisons, it was noted that a word or phrase was rendered differently between the older copies. By reflecting the variation in the margin, the new copy preserves both versions. In some cases, like the one illustrated below, the variations are extremely minor: the exemplar from which this manuscript was produced rendered the word ‘that’ ذلك, whereas another old copy was found to have rendered it ذاك, an alternative Arabic spelling of the same word. This variation has no effect on the text’s meaning, however meticulous scholars of hadith, who were keen to preserve all possibilities of the original wording, valued these marks.

Such annotations to marking slight text variations as recorded in different exemplars also appear commonly in poetry collections. In cases of more significant variation, marks of ‘another version’ can be very useful today to explore variations from manuscripts that no longer exist.

Collation Notes

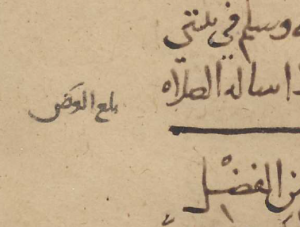

It could take many sessions to read aloud a large manuscript to collate a new copy. Each time the collator stopped his work, he would mark the place, writing a sign to indicate the progress. Conventions usually employed one of the following phrases or abbreviations of them for these marks:

بلغ/بلغت معارضة - buligha(t) muʿāraḍatan - this point was reached in collating

بلغت مقابلة - buligha(t) muqābalatan - this point was reached in comparing

بلغ العرض - buligha al-ʿārḍ the collation reached here

قوبل - qūbila this has been compared

عورض - ūriḍa this has been collated, presented

(note the verb بلغ in the above examples was sometimes vocalised in the active "balagha" or the passive "buligha").

The marks served the copyist or circle of listeners when he/they resumed the work of collation, and the marks also served as a mark of the care in which they text was produced for subsequent readers of the codex.

Sometimes instead of writing the collation formulae, copyists used the symbol Ꙩ to indicate the point reached by a session of collation, but this was not universal practice, and the same symbol Ꙩ was also employed (as in the case of the present manuscript) to indicate any pause or distinction between parts of the text, much as modern English paragraphing functions today).

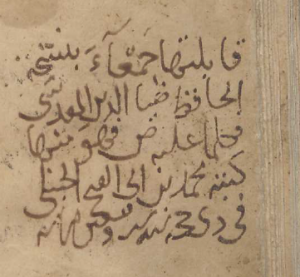

Collation notes in al-Dārimī's al-Musnad

According to notes next to the colophon on f283v, this manuscript was collated at least two times (i.e. submitted to muqābala with other copies). It was read once against the original aṣl (the manuscript of Abū al-Waqt): according to the note, this was done “as well as possible” (ʿalā ḥasab al-imkān), perhaps suggesting that part of this manuscript was illegible, missing, or it is a mark of humility. The second collation is noted with a more detailed note:

قابلته جمعاء بنسخة الحافظ ضياء الدين المقدسي فكل ما عليه ض فهو منها كتبه محمد بن أبي الفتح الحنبلي في ذي الحجة سنة ست و[؟]

“I collated all of this with the copy of al-Ḥāfiẓ Ḍiyāʾ al-Dīn al-Maqdisī; any text marked with a letter ḍad is from that copy. Muḥammad ibn Abī al-Fatḥ al-Ḥanbalī wrote this note in the month of Dhū al-Ḥijja in ??6” (the date is difficult to decipher)

Each of these muqābala collations resulted in additions and observations of ‘different versions’ in the text marked by the abbreviation خ, however, there are several different forms in which this marginal note appears in the manuscript. These different forms may indicate separate instances of collation, or the copyist may not have been consistent in how he marked the different versions. See Question 1 for more on these marks.

The most frequent marks to indicate the checking of this manuscript are written بلغ العرض. This refers to the public presentation of the manuscript before an assembly (the details of these auditions are discussed in Lesson 12). The spacing of these marginal notes give us an indication of the pace by which pre-modern scholars were able to check manuscripts in one sitting (see Assignment 1).

Other marks refer to muqābala comparison with other copies; these marks sometimes specify whether the collation was from an oral audition or done silently by comparing two manuscripts together, and sometimes add further information about the sources collated.

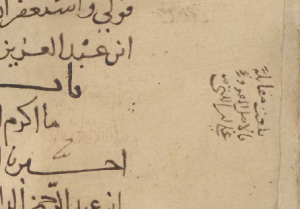

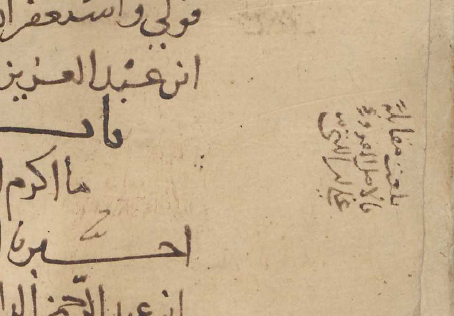

For example, the note illustrated to the right reads:

بلغت مقابلة بالأصل المقروء على يد اللتي

“This is a point where al-Latī’s collation read against the original reached”

The note refers to the reading of the early exemplar of al-Dārimī’s al-Musnad in the presence of the Abū al-Munajjā ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿUmar ibn ʿAlī ibn Zayd ibn al-Latī, and refers to his collation notes (see Lesson 12 for the audition note referring to this scholar).

There are various other detailed marks of collation. Consider another on f. 47v:

سقط من هنا إلى آخر الباب من الأصل المسموع على يد اللتي بجبل قاسيون وقفه الحافظ ضياء الدين

The note refers to a reading done on Mt Qāsiyūn in Damascus, where the version which al-Latī produced in oral audition did not contain a series of hadiths from the point of this note to the end of the chapter; those hadiths were related in the other recension of Ḍiyāʾ al-Dīn al-Maqdisī (the version referred to in the second muqābala note above).

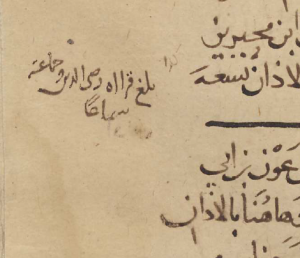

A final collation note to consider is on f. 88r, as it records another common marginal formula in manuscripts:

This note reads: بلغ قراءة رضي الدين وجماعته سماعًا

“Collation read orally from Raḍī al-Dīn and his group”, this refers to the version of al-Dārimī’s al-Musnad narrated by Raḍī al-Dīn al-Muʿāfā, noted in the transmission of the book (see Lesson 11). It specifies that the reading was done before an assembly. See also 98r for another note of this version.

For other collation notes in this manuscript see the Questions and Assignments.

More about this manuscript: lessons 3, 11, 12.

Further reading

A. Gacek, Arabic Manuscripts, a Vademecum for Readers. Brill 2009, 65 ff.

F. Rosenthal, The Technique and Approach of Muslim Scholarship. Analecta Orientalia 24, Rome 1947, 1- 48.

Al-Samʿānī, ʿAbd al-Karīm b. Muḥammad/M. Weismüller, Adab al-imlāʾ waʾl-istimlāʾ. Leiden 1952.

Questions

-

As noted in the lesson, when readers compared the manuscript against different exemplars and noted variations in old texts, they affixed the symbol خ to indicate the variations in the underlying texts. There are, however, several different kinds of annotations for different versions – the abbreviation خ is written differently or with combinations of letters – these may indicate separate exercises of collation with different manuscripts. Look through the marginal notes in the manuscript, and identify how many different forms of these ‘variation’ notes you can find. What might the differences signify?

-

Look at f. 59v, what does the lower annotation in the right margin say, and what does this indicate?

-

Examine the marginal note in the upper-left margin of f. 18r, the two marginal notes in the lower-right margin on f. 26v, and the left margin of f. 27r. What do they say, and why were they added?

Assignments

-

Leaf through the manuscript and write down where you see that presentation was paused (i.e. marked with the بلغ العرض marginal note). How many pages were presented at a time, on average? What is the longest stretch between the marked pauses?

-

Examine the marginal notes on f. 25r and v. Transcribe as much of them as possible and explain what they indicate.