About this manuscript

A popular pharmacopoeia

This is one of the many extant copies of the Minhāj al-dukkān wa dustūr al-aʿyān, a pharmacopoeia (aqrābādhīn, from the Greek graphidion)

or pharmacist’s handbook. The original was written in Cairo in 658/1260

by Abū al-Munā Dāwud ibn Abī Naṣr al-Kūhīn al-ʿAṭṭār al-Isrāʾīlī

al-Hārūnī, who was probably a Jewish druggist. In this collection, he

brought together a large number of recipes based on simple drugs and

compound remedies for an audience specifically committed to

pharmacology, a craft that he distinguished from medical science. The Minhāj al-dukkān continues a long tradition of drug formularies which include works such as Sābūr ibn Sahl’s dispensatory (9th century CE, now lost) and Ibn al-Tilmīdh’s al-Aqrābādhīn al-Kabīr (12th century CE). The variety of the remedies described in the Minhāj, as well as their practicality, are probably among the main reasons for its popularity in the Islamic world. A printed version (but not a critical edition) appeared in 1870 and continued to be used until the 1960s.

Physical characteristics

Or. 1532 was written in a

regular hand. Headings are written with red ink, to help the user to

quickly find the recipe he needs. Almost understandably for a book of

recipes that has been used intensively, the codex is quite worn. The

first and last folios are missing and there is no colophon or other

information about the date or place where the manuscript was produced.

Most of the leaves have been affected by wear and tear and by insects.

Many have been lost altogether, so that the manuscript contains less

than half of the original work. Apart from that, the order of the leaves

has been mixed up, a problem that is exacerbated by the lack of taʿqibāt.

The manuscript has also been restored several times. Holes in the paper

have been repaired (with pieces of paper that have covered some parts

of the text) and the margins have been trimmed (cutting off parts of the

marginal notes). The binding is European.

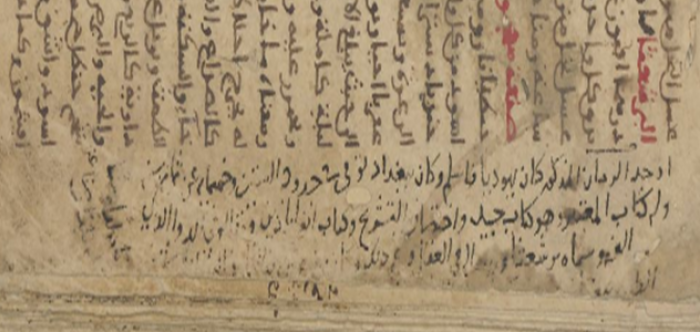

Analysing the marginal notes

With all its defects, Or. 1532 could only make a small contribution towards a critical edition of the Minhāj al-dukkān.

The engagement notes in the margins, however, make this manuscript an

interesting object of analysis. As a first step, we can identify at

least three categories of notes that are related to the main text in

different ways:

Group A is constituted by notes written in the same hand and with the same (brownish) ink as the main text. They are probably the earliest notes, added by the copyist of the manuscript himself. These notes are mostly corrections and additions to the main text. See for instance the note on f 16v (relating to the reference mark or ʿaṭfa on line 2), on f 28v (ʿaṭfa on line 7), on f 37r (ʿaṭfa at the beginning of line 19), f 45v (ʿaṭfa on line 10), f 50r (ʿaṭfa at the beginning of line 5). Many of the corrections concern omissions and we can imagine the copyist at work here, comparing his version with the original or with another version at his disposal.

Group B comprises notes by a pharmacist, it would seem, who has added several recipes in the margins (for instance on f 11v, f 12v, f 27v, f 36r, f 36v). They are not written in the maghribī script like the rest of the manuscript, but in naskh. However, the author of the notes clearly sought to join the style of the main text, by using red ink for the headers (as in the main text) and a black ink for the recipes themselves. Most of these recipes are partly illegible due to the faded ink and trimmed margins and it would be difficult to determine whether they come from another copy of the Minhāj or from a different source altogether.

Group C contains glosses that explain references and names mentioned in the main text (e.g. on f 22r, f 22v, f 47v). In fact, this notes are usually introduced by a حـ for ḥāshiya (gloss – Gacek Arabic manuscripts 314) written over them.

On f 22r for example, we find a gloss that gives bio-bibliographical details about Ibn Jazla, the author of the Minhāj (i.e. the Minhāj al-bayān) mentioned in line 24, saying that he compiled his work during the caliphate of al-Muqtadī (r. 467/1075-487/1094; cf Chipman 30-31).

On f 22v is a gloss that adds information about the name of a complex and semi-mythical remedy, the mithrūdītūs, the recipe for which is given in the main text (line 22). The commentator explains that Mithrūdītūs was the name of a Greek king who lived before Galenus and that the drug named after him was used as an antidote for poisoning and other illnesses.

The gloss at the margin of f 47v provides information about Ibn Sirābīūn, who is mentioned in the main text of the same folium in line 7, as the maker of an electuary (made of burnt scorpions, Greek gentian, Chinese pepper, castoreum and bees' honey) to treat scorpion stings معجون العقارب : here the commentator tells us that Ibn Sirābīūn was a Jew who converted to Islam, that he lived in Baghdad, where he died around 560 AH and authored a pharmacopeia.

Further reading

Andreas Görke and Konrad Hirschler (eds), Manuscript Notes as Documentary Sources, Würzburg 2011.

Questions

-

Look at where the notes were written and note that they were written before the last trimming of the manuscript. But which group of notes is most recent?

Assignments

-

Catalogues and editions often overlook marginal notes. If we want to exploit such notes more thoroughly, it would be helpful if catalogues mention the presence of different types of notes in manuscripts. How could these be best recorded to inspire research? By what sort of categories and what sort of basic information? Write a paper about this question and submit it via Brightspace.

-

Do you see notes in Or. 1532 that do not belong to any of the groups listed above?