About this manuscript

An Islamicate Manuscript?

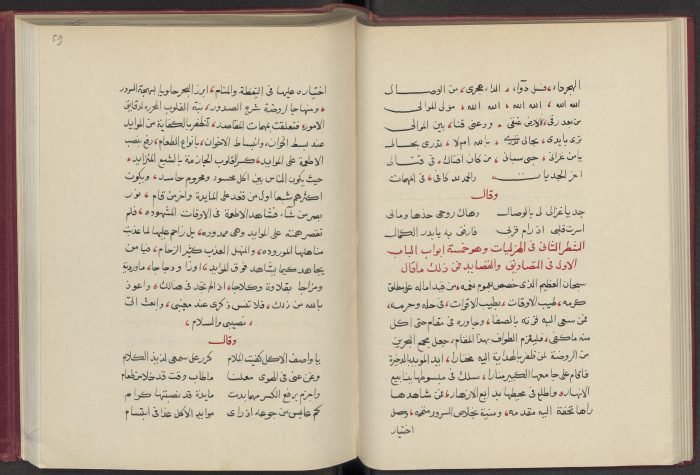

Seen from the inside, the Leiden codex Or. 14.520 looks like a typical Middle Eastern manuscript from the Ottoman era onwards (c.1500-1900 CE). It is written in common black naskh script with some influence of ruqʿa, with rubrication in red ink, 19 lines to the page, with blind ruling and catchwords on every right-hand page. It is written on rather thick machine-made paper without chain lines (‘wove paper’), no watermark, probably of European manufacture. The use of imported European paper in Middle Eastern manuscripts was very common from the fifteenth century onwards. The textblock consists of quinions, with quire signatures in red ink indicated with the Arabic letter kāf (for kurrāsa, quire).

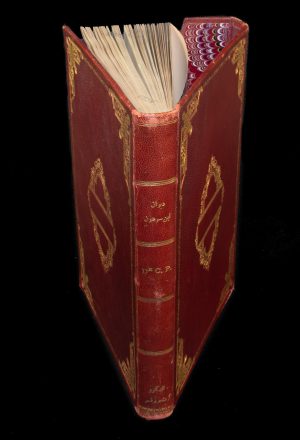

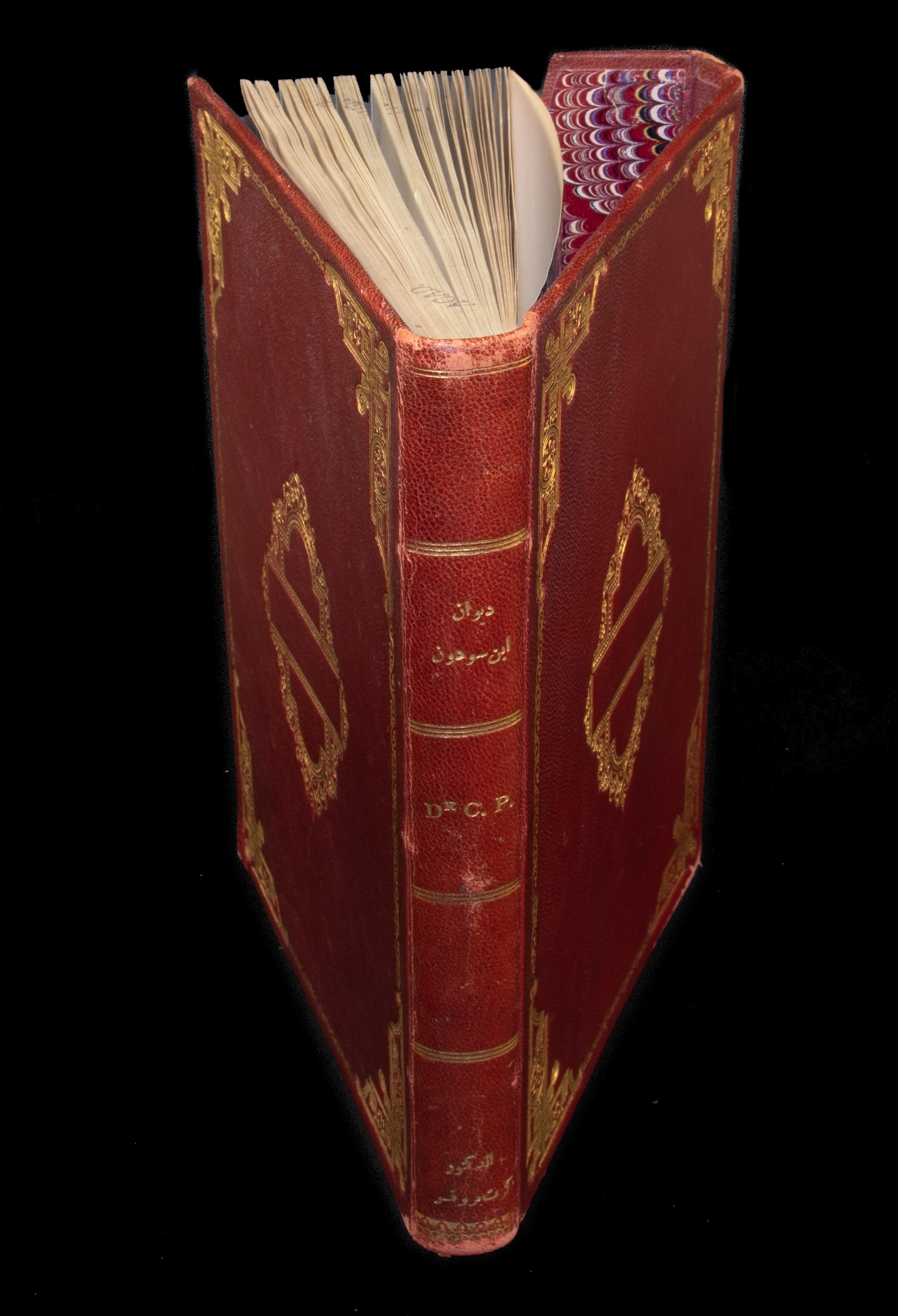

The cover, however, tells a different story that reveals changes afoot in this late period. The cover's envelope flap is as regular Oriental bindings from earlier periods, but otherwise the cover is purely in the European style, with Western gold tooling, a rounded spine with a printed title (sic!), and quires sewn over five stations with prefab stuck-on endbands. The marbled endpapers are also factory made and from Europe. With the help of another binding of identical provenance in the Leiden collections (Or. 14.521) it could be established that the manuscript was bound in Cairo by a certain Richard Preller, probably a German bookbinder.

Provenance

The spine mentions a ‘Dr C.P.’, doubtless the owner of the manuscript. This is the German Arabist Curt Prüfer (1881–1959). Between 1907 and 1914 he was stationed as a diplomat at the German Legation in Cairo, like all foreign missions a hotbed of espionage in the years preceding the First World War. Like many of his German contemporaries such as Friedrich Kern, Martin Hartmann and Paul Kahle, Prüfer was deeply interested in popular Egyptian literature and theatre in the vernacular, which would explain why he acquired such a manuscript. His knowledge of Egyptian Arabic would have served him well in his everyday work as an intelligence officer (Vrolijk 2006).

The Eclipse of the Professional Scribe

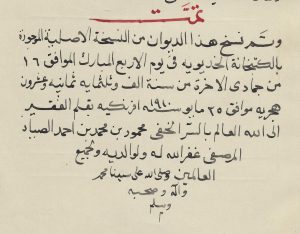

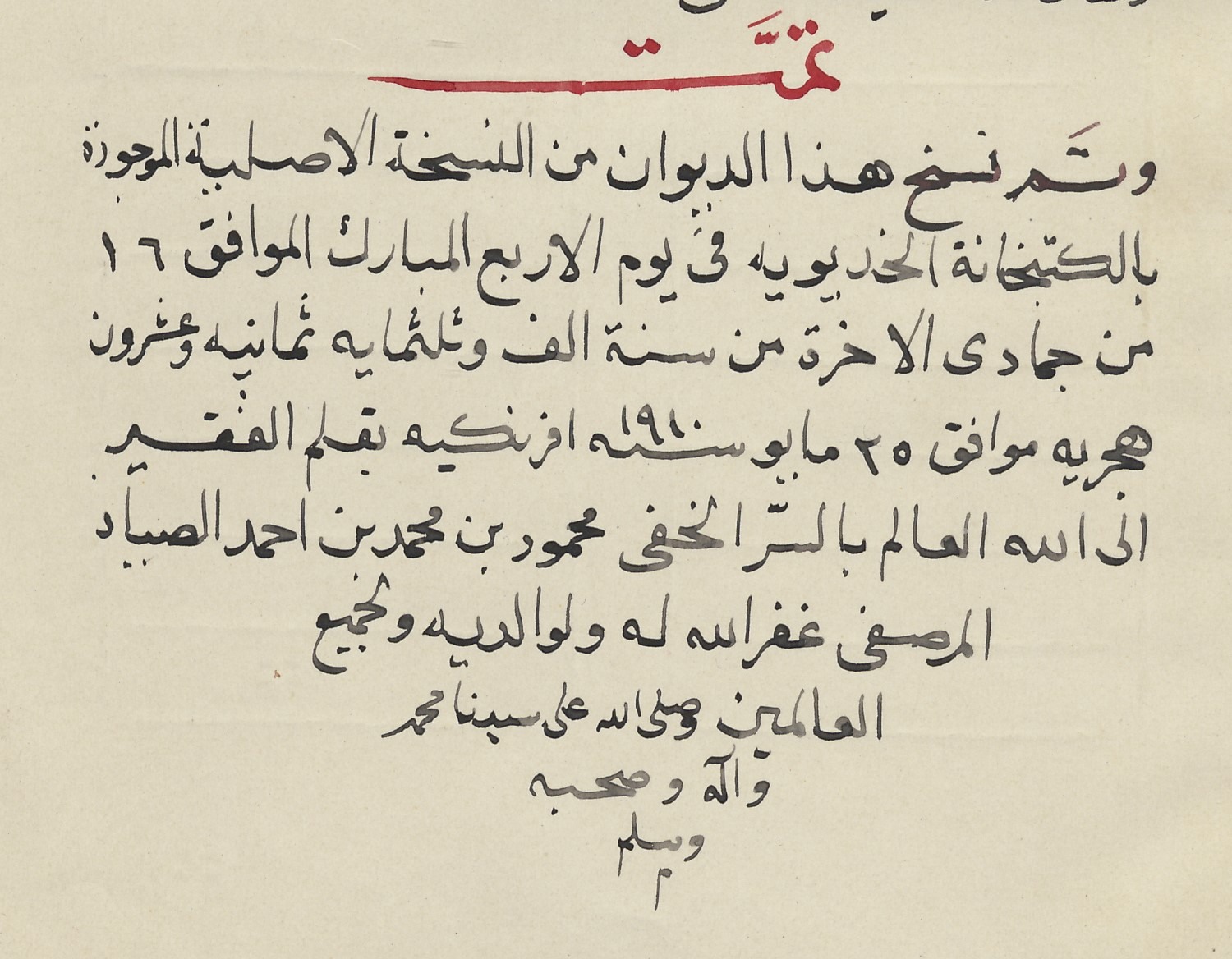

This is an exceptionally late example of an Arabic manuscript and it deserves our attention in various ways. The colophon (f. 181a) states explicitly that the copy was finished on Wednesday 16 Jumādā al-Ākhira 1328 AH, corresponding to 25 May 1910 CE, at the Khedivial Library (al-Kutubkhāna al-Khudaywiyya) in Cairo, the forerunner of the Egyptian National Library (Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya).

The manuscript was copied from a late-sixteenth-century exemplar in the collections of the same library, MS Adab 329 (see Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya, Fihris al-kutub al-ʿarabiyya al-mawjūda bi-ʾl dār, III, p. 410).

The copyist, Maḥmūd ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Ṣayyād al-Marṣafī, was one of the professional scribes at the Khedivial Library who made their services available to the public. They worked at a special desk in the neo-Mamluk building of the library in Bāb al-Khalq, which opened its doors in 1903. In or shortly after 1908 the Russian Arabist Ignaty Iulianovich Kratchkovsky (1883–1951) was copying and collating Arabic manuscripts for his own use at the same desk. Initially his arrival caused an upheaval among the copyists, who believed that he had come as a business competitor. Writing from first-hand observation, he remarked somewhat despondently that

‘the copyists all wore fezzes […]. They were mostly retiring, modest middle-aged men, usually quite uneducated, who seldom understood what they were copying. Some of them were great amateurs of, and in a way experts in, calligraphy for which they no longer found any real application. They were the last representatives of a doomed profession and could not compete with the printing-press or the photostatic copying of manuscripts which was then only just coming into use. Some ten years later they must have been finally defeated by the rapid progress of the typewriter with Arabic script’ (Kratchkovsky 2016, p. 38-39).

But in the mid-1920s the Danish book historian Johannes Pedersen noted that the work of the traditional copyist had still not died out entirely. They were still working at the same desk, ‘where they sat with their pencil-cases and inkstands and transcribed manuscripts with reed pens, which they emphatically preferred to steel pens’. Apparently copyists were poorly paid, but manuscript copies were nevertheless expensive (Pedersen 1984, p. 53).

We do not know precisely when the professional copyists finally left the Dār al-Kutub premises: Ayman Fuʾād Sayyid's history of the Library does not mention this scribal facility, but a service for photostatic copying was created in 1930, followed by microfilming from 1951 onwards (Sayyid 1996, p. 186). These modern developments firmly sounded the death knell for the professional scribe, and today hand-written transcription from manuscripts has disappeared, except in the cases of the odd scholar whom one may still see in library reading rooms patiently transcribing manuscripts from a microfilm reader for their own personal use, as a cheaper alternative to ordering electronic or printed reproductions.

References

Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya, Fihris al-Kutub al-ʿArabiyya al-Mawjūda bi-ʾl-Dār. 9 pts in 10 vols, Cairo: Maṭbaʿat Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya, 1342–1383/1924–1963.

I.Y. Kratchkovsky, Among Arabic Manuscripts: Memories of Libraries and Men, tr. Tatiana Minorsky. Leiden etc.: Brill, 2016.

Johannes Pedersen, The Arabic Book, tr. Geoffrey French. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Ayman Fuʾād Sayyid, Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya: Tārīkhuhā wa Taṭawwuruhā. Cairo: Awrāq Sharqiyya, 1417/1996.

Arnoud Vrolijk, Bringing a Laugh to a Scowling Face: a Critical Edition and Study of the “Nuzhat al-Nufūs wa-Muḍḥik al-ʿAbūs” by ʿAlī Ibn Sūdūn al-Bašbuġāwī (Cairo 810/1407 – Damascus 868/1464). Leiden: CNWS, 1998. Online via http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1990495.

Arnoud Vrolijk, ‘From shadow theatre to the Empire of Shadows: the career of Curt Prüfer, Arabist and diplomat,’ Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 156/2 (2006), p. 369-378.

Questions

-

Where was the Khedivial Library based before it moved to its new premises in Bāb al-Khalq?

-

Where do the references to the author of this lesson's text appear in Brockelmann’s Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur? (an English translation of Brockelmann's work is also available from Brill online)

-

Double check the Hijrī date and its Gregorian conversion in the colophon on f. 181a - are they correct?

Look up the date on the manuscript and use the online calendar converter tool (https://calendarhome.com/calculate/convert-a-date/) or (https://www.aoi.uzh.ch/de/isla...)

-

As is relatively common, this manuscript preserves the colophon of the exemplar manuscript from which this copy was made. Find and translate the colophon of the sixteenth-century exemplar in MS Leiden Or. 14.520, working your way backwards from the second colophon from 1910 on f. 181a.

-

Brockelmann lists two closely related versions of the work of Ibn Sūdūn: Nuzhat al-nufūs wa-muḍḥik al-ʿabūs and Qurrat al-nāẓir wa-nuzhat al-khāṭir. Read the author’s introduction on ff. 3a-4a of the Leiden MS Or. 14.520: what does it say about the text's development?